To Hell and Back

You're traveling through another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That's the signpost up ahead—your next stop, the Twilight Zone!

Actually, this desolate, listing signpost is at Freezeout Saddle on the edge of Hells Canyon in eastern Oregon, but it’s always nice to have an excuse to quote from The Twilight Zone and there were some Twilight Zone-ish elements to our trip (discussed and depicted in previous entries), so I think it’s legit to reference "The Zone."

Hells Canyon was as far east as we got. It’s as far east as anyone gets in Oregon without plummeting into the Snake River and floating over to Idaho—something we elected not to do.

The one thing I wanted to be sure to write about was the National Monuments we visited on our trip. National Monuments are the great unsung heroes of the National Park/USDA Forest Service/Bureau of Land Management troika. For some reason, known only to the troika, National Monuments don’t quite merit National Park status, and I say “thank god!” for that. If they were National Parks, there would be scads of RVs shilly-shallying their way through them and degrading the environment with copious amounts of greenhouse gases and just generally ruining my wilderness experience.

National Monuments just don’t seem to be on the radar screen for most people. What are they anyway? A “National Monument” could be anything. My theory is that most people have the notion that National Monuments are birdpoop-covered statues of some guy they’ve never heard of or boulders with plaques on them commemorating some event they’ve never heard of. The term “National Monument” is just too ambiguous and vague. Rather than stop at a National Monument, most folks probably prefer to keep driving toward something less abstract—like a Dairy Queen.

Doing so, however, means foregoing a hike through these stupendous blue badlands (at the Sheeprock Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument)

and missing the Painted Hills (also part of the John Day Fossil Beds NM)

How can a Dilly Bar or a Peanut Buster Parfait trump that?

It is true that a few people do check out the National Monuments, but they tend to carom from scenic viewpoint to scenic viewpoint, stopping for no more than a few minutes before driving to the next one.

Now I don’t expect everyone to relish launching out on trails that head straight up, but many perfectly able-bodied people won’t even get out of the car to take a 10-minute stroll down a flat, wheelchair-accessible trail. I timed one couple that drove up at one of these viewpoint/trailheads. They got out of the car, walked over to the interpretive sign (which they ignored), aimed their camera at “the view,” and then got back in the car and sped off. Total amount of time spent outside of the car: 50 seconds. Unbelievable.

When people opt for that sort of an experience they cheat themselves out of so much. At Newberry Crater National Monument, for example, B and I took an 8-mile hike around Paulina Lake—a collapsed, water-filled caldera that’s a mile above sea level. Along the trail, we climbed a cinder cone, traversed a field of glinting black obsidian that clinked like broken beer bottles as we crossed it, and took a dip in a natural hot spring, all while breathing in pure mountain air and viewing jagged Paulina Peak from every possible angle. But that’s not all. Near the end of the hike we stumbled across this wonderfully rustic restaurant/bar that’s part of an old-timey resort tucked away in the woods.

It was a bit of a Twilight Zone moment, come to think of it--it felt like we’d been transported back to the 1950s or perhaps even earlier. This is what it looked like inside. And here’s the resort’s little store. I was just so charmed by all of it. Plus, how often do you get a chance to stop for a beer without leaving the trail? It was a first for me.

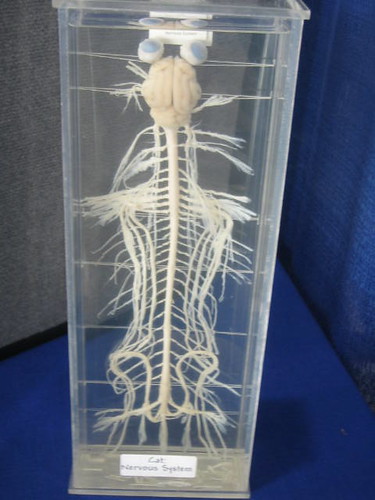

So this is the kind of thing the people who choose to bypass national monuments miss out on. Apparently, not many people are interested in the Oregon Trail either, because attendance at the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center (brought to us by the Bureau of Land Management) just outside Baker City was quite sparse. And the interpretive center was truly outstanding. They had these exhibits with pioneer figurines (presumably fitted with hidden electric eyes) who would suddenly start talking to you, that is, telling you their story. Just to be clear: these were not real people dressed up as pioneers but realistic manniquins. And when I say “realistic” I mean their clothes were tattered, filthy, and stained with sweat under the armpits. Cow and horse dung (possibly the real stuff with a coat of shellac on it) lined the trail, and the livestock’s noses were shiny as if wet with mucus and/or spittle. I appreciate it when someone strives that hard for authenticity.

You may be thinking: Wasn’t it just the cheesiest thing ever? In fact, no. Somehow, despite the admittedly high potential for cheesiness, they managed to sidestep it. Plus, the exhibits were interactive in a very low-tech, noncomputerized way, which of course wins points from me. Text-based exhibits would pose questions the pioneers would have faced, i.e., do you take that big-ass cast-iron stove you bought in St. Louis and paid so much money for or do you leave it behind? You then make your decision and lift a wooden panel to see if you made the “right” choice. As you probably guessed, taking the iron stove was a boneheaded idea, but plenty of pioneers took them and soon regretted it. Apparently, the early segments of the trail were littered with cast-off stoves (and lots of other cumbersome items people had been foolish enough to bring). Anyway, I found all these “what would you do”-type questions to be highly engaging and informative. I also came to the conclusion that I would have lasted about one day on the Oregon Trail before saying, “Fuck it, I’m going back to Chicago.” I’m glad we were able to travel to Oregon in style in the 1989 Honda Civic instead of jolting along in this thing.

The other smart thing they did was to include lots of primary source material (e.g., diaries and letters written by actual pioneers) in the explanations and the short films they had playing here and there. Probably the coolest thing was that you could take a 3-mile hike to a section of the actual trail where the wagon-wheel ruts are still visible. Amazing to think that they’re still there after more than 100 years!

This is probably all I’m going to write about our trip to central and eastern Oregon. I haven’t said hardly anything about the fantastic hikes we took in the Three Sisters Wilderness, the Blue Mountains, the Wallowa Mountains, and the Eagle Cap Wilderness (we hiked every day), so if you want to see some more photos, click here for a slide show. It will take about two minutes to view.

Actually, this desolate, listing signpost is at Freezeout Saddle on the edge of Hells Canyon in eastern Oregon, but it’s always nice to have an excuse to quote from The Twilight Zone and there were some Twilight Zone-ish elements to our trip (discussed and depicted in previous entries), so I think it’s legit to reference "The Zone."

Hells Canyon was as far east as we got. It’s as far east as anyone gets in Oregon without plummeting into the Snake River and floating over to Idaho—something we elected not to do.

The one thing I wanted to be sure to write about was the National Monuments we visited on our trip. National Monuments are the great unsung heroes of the National Park/USDA Forest Service/Bureau of Land Management troika. For some reason, known only to the troika, National Monuments don’t quite merit National Park status, and I say “thank god!” for that. If they were National Parks, there would be scads of RVs shilly-shallying their way through them and degrading the environment with copious amounts of greenhouse gases and just generally ruining my wilderness experience.

National Monuments just don’t seem to be on the radar screen for most people. What are they anyway? A “National Monument” could be anything. My theory is that most people have the notion that National Monuments are birdpoop-covered statues of some guy they’ve never heard of or boulders with plaques on them commemorating some event they’ve never heard of. The term “National Monument” is just too ambiguous and vague. Rather than stop at a National Monument, most folks probably prefer to keep driving toward something less abstract—like a Dairy Queen.

Doing so, however, means foregoing a hike through these stupendous blue badlands (at the Sheeprock Unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument)

and missing the Painted Hills (also part of the John Day Fossil Beds NM)

How can a Dilly Bar or a Peanut Buster Parfait trump that?

It is true that a few people do check out the National Monuments, but they tend to carom from scenic viewpoint to scenic viewpoint, stopping for no more than a few minutes before driving to the next one.

Now I don’t expect everyone to relish launching out on trails that head straight up, but many perfectly able-bodied people won’t even get out of the car to take a 10-minute stroll down a flat, wheelchair-accessible trail. I timed one couple that drove up at one of these viewpoint/trailheads. They got out of the car, walked over to the interpretive sign (which they ignored), aimed their camera at “the view,” and then got back in the car and sped off. Total amount of time spent outside of the car: 50 seconds. Unbelievable.

When people opt for that sort of an experience they cheat themselves out of so much. At Newberry Crater National Monument, for example, B and I took an 8-mile hike around Paulina Lake—a collapsed, water-filled caldera that’s a mile above sea level. Along the trail, we climbed a cinder cone, traversed a field of glinting black obsidian that clinked like broken beer bottles as we crossed it, and took a dip in a natural hot spring, all while breathing in pure mountain air and viewing jagged Paulina Peak from every possible angle. But that’s not all. Near the end of the hike we stumbled across this wonderfully rustic restaurant/bar that’s part of an old-timey resort tucked away in the woods.

It was a bit of a Twilight Zone moment, come to think of it--it felt like we’d been transported back to the 1950s or perhaps even earlier. This is what it looked like inside. And here’s the resort’s little store. I was just so charmed by all of it. Plus, how often do you get a chance to stop for a beer without leaving the trail? It was a first for me.

So this is the kind of thing the people who choose to bypass national monuments miss out on. Apparently, not many people are interested in the Oregon Trail either, because attendance at the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center (brought to us by the Bureau of Land Management) just outside Baker City was quite sparse. And the interpretive center was truly outstanding. They had these exhibits with pioneer figurines (presumably fitted with hidden electric eyes) who would suddenly start talking to you, that is, telling you their story. Just to be clear: these were not real people dressed up as pioneers but realistic manniquins. And when I say “realistic” I mean their clothes were tattered, filthy, and stained with sweat under the armpits. Cow and horse dung (possibly the real stuff with a coat of shellac on it) lined the trail, and the livestock’s noses were shiny as if wet with mucus and/or spittle. I appreciate it when someone strives that hard for authenticity.

You may be thinking: Wasn’t it just the cheesiest thing ever? In fact, no. Somehow, despite the admittedly high potential for cheesiness, they managed to sidestep it. Plus, the exhibits were interactive in a very low-tech, noncomputerized way, which of course wins points from me. Text-based exhibits would pose questions the pioneers would have faced, i.e., do you take that big-ass cast-iron stove you bought in St. Louis and paid so much money for or do you leave it behind? You then make your decision and lift a wooden panel to see if you made the “right” choice. As you probably guessed, taking the iron stove was a boneheaded idea, but plenty of pioneers took them and soon regretted it. Apparently, the early segments of the trail were littered with cast-off stoves (and lots of other cumbersome items people had been foolish enough to bring). Anyway, I found all these “what would you do”-type questions to be highly engaging and informative. I also came to the conclusion that I would have lasted about one day on the Oregon Trail before saying, “Fuck it, I’m going back to Chicago.” I’m glad we were able to travel to Oregon in style in the 1989 Honda Civic instead of jolting along in this thing.

The other smart thing they did was to include lots of primary source material (e.g., diaries and letters written by actual pioneers) in the explanations and the short films they had playing here and there. Probably the coolest thing was that you could take a 3-mile hike to a section of the actual trail where the wagon-wheel ruts are still visible. Amazing to think that they’re still there after more than 100 years!

This is probably all I’m going to write about our trip to central and eastern Oregon. I haven’t said hardly anything about the fantastic hikes we took in the Three Sisters Wilderness, the Blue Mountains, the Wallowa Mountains, and the Eagle Cap Wilderness (we hiked every day), so if you want to see some more photos, click here for a slide show. It will take about two minutes to view.